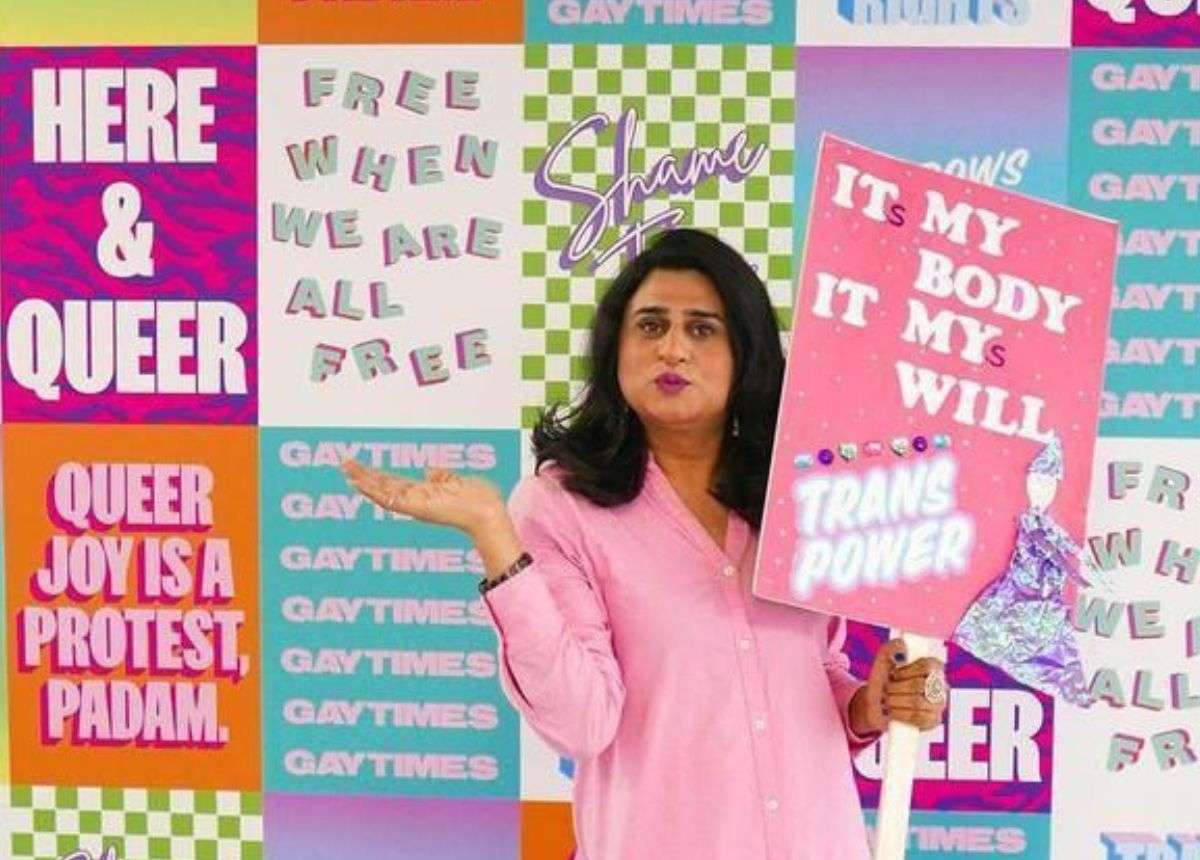

Marina’s journey to freedom

Some people may find the topics discussed in this article triggering. This article reflects people’s stories and the hardships they have faced. If you are an LGBTQI+ person seeking asylum and would like to access emotional support please contact us.

Marina left Cameroon because her family discovered her sexual orientation. She was forced into a relationship with a man, and despite going to the police received no help – in fact, they threatened to lock her up. “My life was in danger”, she says “so that’s when I decided to leave Cameroon”.

When she came to the UK, Marina’s only goal was “just to get out of Cameroon”. Marina arrived as a student and didn’t know anything about the asylum process. But when her student visa expired and she received a letter from the Home Office threatening her with removal, Marina knew she couldn’t go back to Cameroon. In desperation, she started calling friends, asking if anyone had any idea what she could do. One friend mentioned knowing a gay man from Cameroon who had recently been granted asylum in the UK and offered to put her in contact with him. Marina jumped at the opportunity.

The friend told Marina that he attended a meeting for LGBTQI+ people seeking asylum in Glasgow. For a while, Marina attended these meetings too, despite living in London. She would often travel 12 hours each way to attend a meeting for a few hours in the evening. Eventually, the stress of this became too much “and one day I said ‘if there are groups in Glasgow there should be groups in London I swear’”. That’s when Marina found Rainbow Migration.

Marina attended a Rainbow Migration monthly asylum meeting, where she was able to speak to a lawyer. She had heard about detention and deportation, and she was very afraid of what could happen to her. The lawyer encouraged her to claim asylum and gave her a list of people to contact.

“My life was in danger, so that’s when I decided to leave Cameroon”.

Marina started her asylum claim in April 2019, but didn’t have her substantive interview until May 2021, more than two years later. She emphasises how stressful the waiting is, and how little freedom you have as a person seeking asylum: “I’ve never been so stressed and worried and depressed as in those two years in my whole life”. Marina also describes how hard it is to live on the £38 a week she received from the Home Office, “What can you do with that? You can do nothing. You have to use a bus pass, buy things for the house, you have to eat, you have to clothe yourself, buy coats, jackets, sanitary products, if you have a cold, you have to buy medication, there’s always something you have to buy. It’s draining honestly.”

When it finally came to her interview, Marina says she was lucky that it only took two hours, since she knows people who were interviewed for much longer. In her interview, she was asked repeatedly why she didn’t claim asylum immediately, but Marina never knew this was an option until she met someone who had done it. “It’s not something they advertise”, she explains, and even now she says her friends who aren’t asylum seekers have never heard of claiming asylum on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity.

“You find yourself forced to do things that you don’t want to do just because you want to prove that you are who you are.”

Although her interview went quite smoothly, Marina still found the process of having to ‘prove’ her sexual orientation very difficult. “It’s like trying to prove that I am called my own name”, Marina says when I ask about this. She describes the total loss of privacy that came from having to share conversations with her girlfriend with a lawyer, or detail traumatic experiences like rape to a total stranger: “You find yourself forced to do things that you don’t want to do just because you want to prove that you are who you are.” Marina also notes that expectations the Home Office puts on LGBTQI+ asylum seekers, like going clubbing or using dating apps, are rooted in British culture and norms, so aren’t relevant or appropriate for many people seeking safety here.

Throughout Marina’s experience of the asylum process, she says Rainbow Migration “helped a lot”. From the first meeting she attended “the way they received me was so welcoming. You know you’ve got somewhere”. Marina also joined the women’s group, which helped a lot with isolation, allowing her to meet people who understood what she was going through. Her support worker also helped Marina with accommodation, since the Home Office was planning to send her out of London, where she had lived since arriving in the UK, to somewhere she “knew nobody” and had no support network. Rainbow Migration was able to secure Marina local housing and stop her being isolated from her community, which was really important for her.

Now that Marina has been recognised as a refugee, she says she is happy she can finally move on with her life. She has a job lined up at another organisation that supports migrants and refugees, which she hopes to start once she’s received a written letter confirming her status.

Other stories

Vladimir’s story

Story

Miki’s story

Story

Adams’ story

Story

Staycey’s story

Story

Manono’s story

Story

Saliha’s Story

Story

Nisha’s story

Story