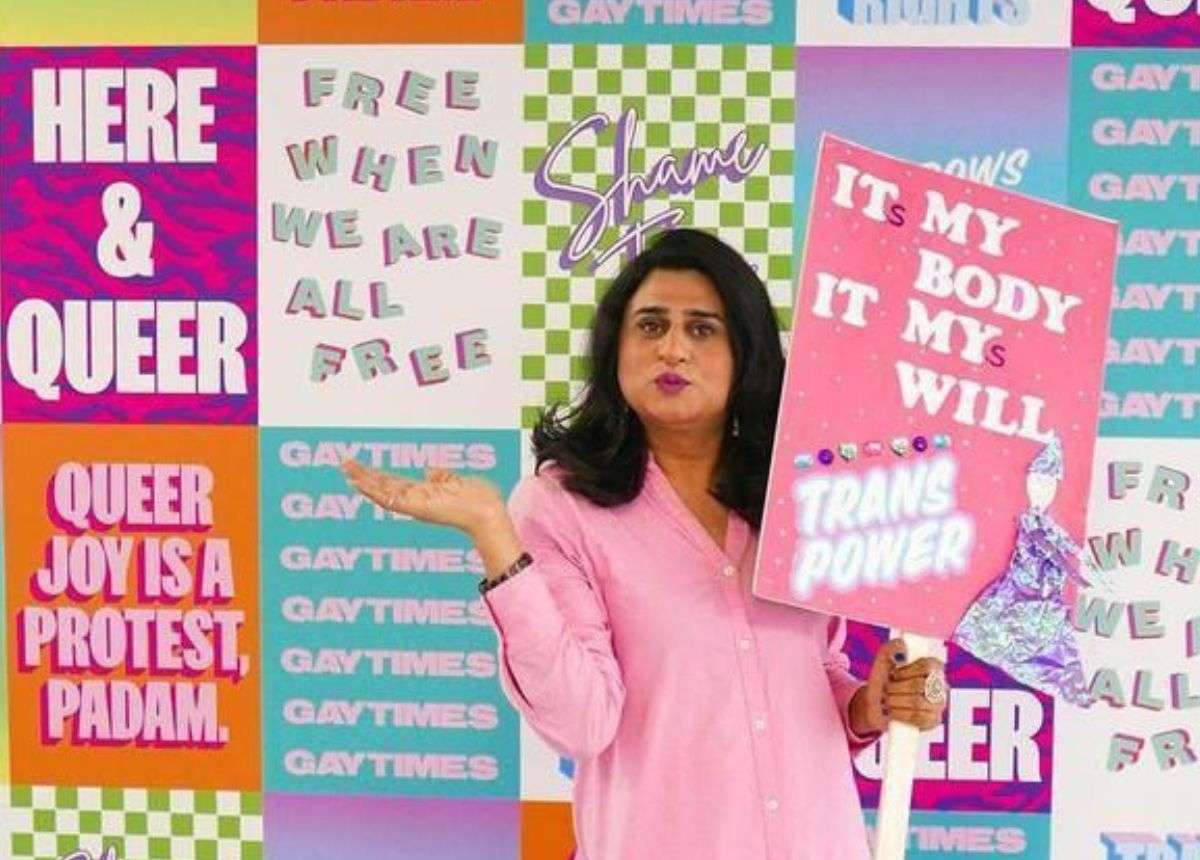

Saliha's Story

Some people may find the topics discussed in this article triggering. This article reflects people’s stories and the hardships they have faced. If you are an LGBTQI+ person seeking asylum and would like to access emotional support please contact us.

Saliha left Bangladesh in 2010 due to political persecution, and ultimately claimed asylum on the grounds of this, her sexual orientation, and her experience as a trafficking victim. Here, Saliha explains her experiences as an LGBTQI+ person in Bangladesh, and her journey to claiming asylum, as well as the community she found through Rainbow Migration.

Growing up in a Muslim family in Bangladesh, Saliha understood that she had to hide who she was. Saliha explains that in Bangladesh, being a part of the LGBTQI+ community is seen as a “curse, it could be some dead thing sitting inside of you”, and that she didn’t have the language to describe her experience, even though she knew her feelings were different. She also mentions that she was sexually abused by a family member as a child, which further undermined her confidence and encouraged her to hide herself. Saliha did try to express that she “loved someone different”, but says she was made to feel like this wasn’t “countable” and disbelieved by her family and community.

At junior high school, Saliha experienced her first love. The pair were friends at first, but a physical and romantic attraction developed between them. Saliha says they were put in a room together to study, but “obviously we didn’t just study”. Saliha describes this relationship as the happiest time in her life, and says that even to this day, if her first love appeared in front of her “I would forget what day is today, I would even forget time”.

However, before the end of junior school, the relationship was discovered by the school, and the two were separated. They were told it was bad for the reputation of the school, and of their families. Saliha also mentions being beaten, and that both girls feared for their safety if their parents were told. But for Saliha, being separated was the most painful part, especially because the girls would still see each other every day but couldn’t talk or even sit on the same bench. Saliha describes the immense pain of seeing the other girl’s eyes, red and swollen from crying

After they left the school, the two girls got back in touch, exchanging loving letters and speaking over the landline. But then the other girl’s brother found one of these letters and reacted badly. She denied to Saliha that her brother beat her, but Saliha says she heard from other people that he did. The brother also spread cruel rumours about Saliha to tarnish her reputation in the community, telling people that she was mad. Saliha’s family questioned her about this, but she says she couldn’t tell them the answer they wanted to hear, because she refused to deny her orientation. Saliha hoped that her aunty, who she was close to, would understand, but says she “also shut her door to me.”

“I said I need to be free, and I got free.”

It was after this rejection by her aunty that Saliha attempted suicide. She says she thought “if I just get out of the world, it will help me.” Saliha’s family didn’t listen to her, and she didn’t feel that her feelings were a priority to them. Following the suicide attempt, Saliha was hospitalised, and she attended therapy. In her community, psychotherapy and counselling were very stigmatised, and seen to bring shame on the family, so she travelled to another city to have counselling. Even here, however, Saliha couldn’t be open about her identity. She says she didn’t feel able to tell her doctor the reasons she was so angry or upset, or why she made the attempt, particularly because he was also from her community.

After that, Saliha went to college and got involved in politics, which was the start of the process which led to her leaving Bangladesh in 2010. Saliha was part of the opposition party, and the party’s leader was arrested, which led to a demonstration. She wasn’t directly involved with the protest, but she was still arrested and injured by police violence in the process. At a hearing in 2014, when she was out of the country, Saliha was sentenced to life imprisonment. She sees this as symptomatic of corruption in Bangladesh, emphasising that she was punished for no reason, just because the government “don’t want you to see how political we were being.”

When Saliha left Bangladesh in 2010, she was on a student visa, and says she was “running from everything…running from life…running from the government.” Throughout this ordeal, Saliha still did not forget her first love, still looking for her “in the paper, everywhere.” In 2014 or 2015, Saliha heard that she had married a man (“of course”), and the two briefly spoke through a neighbour. Saliha suggested she could help her get out of Bangladesh, but “she just answered me it’s not possible…I don’t dream anymore, it’s not possible.” Saliha says she respects her choices, especially because she has children now, and she knows even their communications could ruin her life. However, she still can’t let her feelings fade, although her friends have encouraged her to let it go, and she looks for the same thing in other women, even now.

“I feel blessed to have had support from Rainbow Migration.”

After her student visa expired, Saliha became a victim of trafficking. She says she met a man who claimed he could help her resolve her problems in Bangladesh, and she wanted to see her country and family again. Instead, she ended up sleeping in a bathtub, doing things she doesn’t want to disclose. They moved between houses regularly, but eventually, in the last house, Saliha got to know a girl who ultimately helped her escape. They slipped out at 3am, carrying nothing. However, the man who had trafficked them continued pursuing the pair, contacting people they knew. For safety, Saliha says she barely left the house for a full year.

In 2016, Saliha applied for asylum, but she found the process intimidating and confusing. At first, she put in the wrong application. Saliha also had to speak to the police, and was scared that she might be going to jail. She says that at the time, she didn’t even realise that her experience constituted trafficking. The legal process went over her head, and she wasn’t sure she should tell the truth about her identity or background, thinking, “Should I tell it? I should hide it.”

Around this time, Saliha discovered Rainbow Migration. Saliha describes feeling alienated by other migrants from Bangladesh, particularly as a woman. She also says that she had attended a small LGBTQI+ group, but felt that she didn’t feel she fit in there, due to her unique experiences. Someone there told her about a community for LGBTQI+ migrants, Rainbow Migration, and she went to a meeting for the first time. Saliha says this felt like coming home, and that she had found somewhere where “someone is talking in my language…talking about my feelings.” Saliha attended the women’s group, where she says she witnessed people “opening their hearts to one another.” She describes the community she found at Rainbow Migration as part of her family and says that they gave her the drive to keep fighting back when she came close to giving up.

Saliha was granted asylum in 2020, after a drawn-out court process that she describes as “killing time.” She says the judge finally understood where she was coming from, and that she didn’t even read the final judgement to learn why her application had been accepted, she just wanted the process to be over. Saliha says she struggles to feel happy about the judgement, saying that after so much trauma her emotions are “frozen”, and she still struggles with flashbacks and can’t help but reflect and question why she has had to suffer so much. She says she still sometimes can’t believe she’s alive.

However, Saliha says that she is trying to improve and “come out of it” every day, even though she knows she may never be totally free from her trauma. She has recently completed a 12-week programme of counselling, and she has good friends, including her ex-girlfriend. She also dates “a lot of girls”, but she’s yet to find someone who lives up to her first love (“it might be that we just haven’t met”). Through everything, Saliha says she feels blessed to have had support from Rainbow Migration and that she misses the friends she made there.

Other stories

Vladimir’s story

Story

Miki’s story

Story

Adams’ story

Story

Staycey’s story

Story

Manono’s story

Story

Nisha’s story

Story